Lesotho’s oldest milling company, Lesotho Flour Mills (LFM), is once again in the spotlight for the wrong reasons after management informed staff of fresh retrenchment plans that could see about 25 workers lose their jobs.

The announcement, which came as a shock to many employees, marks the second round of job cuts in less than six months. Workers had hoped that the previous layoffs would help stabilise the struggling company, but the latest development has dashed those expectations.

Some employees who spoke to the media on condition of anonymity described the atmosphere at the company as tense and uncertain. They said staff have not been informed of the criteria for the retrenchments, leaving everyone anxious about their future. “We are all in fear,” one worker lamented. “We are stressed and fear we will soon add to the country’s already high unemployment statistics.”

Lesotho continues to face a high joblessness rate, especially among youth and women. The new job cuts at LFM, which is considered a key employer in the country, are expected to worsen the situation if management proceeds with the retrenchment plan.

Efforts to get clarity from the company’s Chief Executive Officer, Fourie Du Plessis, did not yield much. He declined to speak, saying he could not grant interviews without approval from the board. He, however, confirmed that discussions are still ongoing and that a meeting will be held soon.

The looming retrenchments highlight the deep financial challenges that have haunted LFM for years. Sources within the company point to stiff competition from smaller millers, who flood the market with cheaper unfortified maize meal, as one of the main reasons behind the decline. LFM, which positions itself as a producer of fortified and higher-quality flour, has reportedly been unable to sell its products at competitive prices.

An insider explained the dilemma: “After buying maize from local farmers for three months, we are unable to sell it at a standard price and still make profits.” The result has been heavy financial losses that have forced management to consider layoffs as a survival measure.

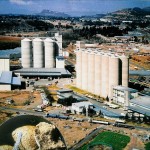

Beyond competition, LFM’s woes are linked to structural and governance issues. The company, which was established in 1979 to support farmers and commercialise Lesotho’s agricultural output, has not declared dividends to the government – which owns a 49 percent stake – for more than 20 years. Analysts argue that this raises serious concerns about accountability and corporate governance.

The company’s majority shareholder, Seaboard Corporation of the United States, holds 51 percent. Insiders allege that Seaboard’s operations worsen LFM’s financial strain. They say that while Seaboard or its subsidiaries allow delayed payments for imports, local farmers demand immediate cash, putting the company in constant debt. “Seaboard allows us to pay after three months, but we must pay local farmers now. We are stuck with loans and wouldn’t be surprised if we get shut down tomorrow,” one worker revealed.

Another issue is the alleged diversion of funds meant to support agricultural production. According to LFM’s Dividend Policy, part of the money should be allocated to the Ministry of Agriculture to boost crop production. Insiders, however, claim that these funds often end up financing other unrelated government programmes, leaving farmers unsupported and the company in further difficulty.

Experts believe that alleged mismanagement, boardroom politics, and incompetence are at the heart of the company’s long decline. They point to provisions under the Companies Act No. 18 of 2011, which allow directors to be held personally liable for losses caused by failure in their duties. Yet, no LFM director has ever been held accountable for the company’s poor performance.

Lesotho Flour Mills was once a symbol of national pride, providing flour, maize meal, animal feed, and later expanding into sugar packaging. But since government sold a controlling stake to Seaboard Corporation in 1998, its fortunes have dwindled. Today, instead of being a lifeline for local farmers and a backbone for the food industry, LFM has become a company on the brink, with employees unsure if their jobs will survive the next round of restructuring.

For a country that depends heavily on agriculture and food security, the uncertain future of Lesotho Flour Mills has raised wider concerns about the sustainability of national institutions. Whether government and shareholders will step in to rescue the company remains to be seen, but for now, the survival of one of Lesotho’s most important agribusinesses hangs in the balance.