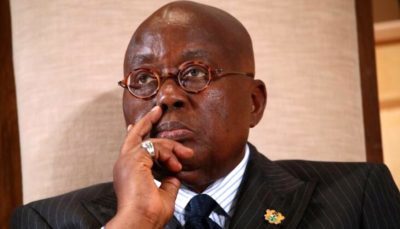

When Ghana’s President Nana Akufo-Addo took to the airwaves in October to assure investors that their money was safe, it was only natural for them to smell trouble ahead. This is exactly what they got.

Long considered one of the most stable and best-run countries in Africa, Ghana is about to join the list of countries that cannot pay its debts. This list is likely to be long. Zambia has already defaulted, and the International Monetary Fund believes that 19 economies in Africa alone are in debt distress.

The government was in denial. “There will be no haircut,” Akufo-Addo stated emphatically. It was left to junior ministers to explain the news that bondholders can expect short backs and sides – and lose about 30 per cent of their tufts in the process.

Ghana’s story highlights the likely fate of other emerging economies as the tide of cheap money recedes. Many got involved in international bond issues with the opening of the capital markets some 15 years ago.

Ghana issued its first international bond, for $750m, in 2007 – and since then it has been returning to the punchbowl. Now, with interest rates normalizing and investors’ appetite for frontier risk waning, the pot has been dumped. When US Treasury yields were less than 2 per cent, Ghana could borrow at 8 per cent or less. The implied rate on its bond is now close to 40 per cent, says Charles Robertson of Renaissance Capital, meaning investors consider it too risky to lend at all.

This is difficult because Ghana, and countries like it, need the money more than ever. Damaged by covid and the cascading effects of the war in Ukraine, economies have stalled and many people have been pushed into poverty.

But far from addressing these problems through spending, Ghana will have to make cuts to appease creditors and the International Monetary Fund, from which Accra is seeking $3 billion. In a way, it will have to protect the most vulnerable while tightening it up financially. Multilateral agencies will have to cut some slack.

Ghana was quick to blame anyone but herself. Akufo-Addo spoke of the confluence of “malignant forces”. A series of external shocks has already made the world a hostile environment. Rich countries, having been promised vaccines and financing, have abandoned Ghana in the midst of the pandemic.

However, the government protests a lot. In February, Moody’s downgraded Ghana’s sovereign debt from B3 to CAA1, prompting it to enter junk territory, attacking Accra Messenger. The finance ministry has accused the rating agencies of mispricing risks in “what appears to be an institutional bias against African economies”.

It was better to look in the mirror. Moody’s debt has reached 80 per cent of GDP, and half of government revenue will be swallowed up by debt interest payments. One Moody’s executive found plans to address worsening finances with arcane spending cuts and an unpopular tax on electronic transactions “extremely ambitious” — which read “total fantasy”. Her cynicism has proven justified.

Ghana had some promising ideas. She made school free until high school. It has cured energy shortages and has some of the best health and well-being indicators in Africa. But spending always escalated before elections. Much of the debt went as a result of the mounting public sector wage bill.

The aim of borrowing should be to improve productive capacity and with it the ability to repay loans. Ghana’s government has frequently indulged in vanity projects, exemplified by plans to build a massive cathedral. Perhaps she hopes that if she prays she can pay her debts.

Plans to clean up messes don’t seem more realistic. Bright Simmons of the Emani think-tank called the latest budget a “Frankenstein mix.” Making public servants drive smaller cars, one proposal, wouldn’t cut it. Nor has the government learned humility. It blames the 50 per cent drop in Sidi this year on “speculators” and the black market. He might instead look at his unfunded deficit and the hum of the presses.

Accra desperately needs a credible plan to get its finances back on track. That would mean crafting a debt restructuring package with creditors and accepting its exclusion from the debt markets.

However, all is not lost. Ghana has solid foundations to build on. It has one of the best-educated workforces on the continent, a reasonably diversified economy, decent infrastructure, and a strong democratic record. This means that the ruling party may be punished in the 2024 elections. But the markets, in time, will forgive and forget. Just ask Argentina.

david.pilling@ft.com