Three researchers from Machakos County have taken their fight to the Kenyan Senate, seeking urgent protection for their rights to continue researching and commercializing a traditional, non-animal plasma-based anti-venom. The scientists—Patrick Musilu, Tom Babu, and Alfred Dosso—claim that they are facing obstruction, intimidation, and unethical demands from various government agencies, particularly the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI).

In a petition tabled in the Senate, the researchers said that in 2021, a KEMRI official allegedly demanded a bribe of KSh 100,000 and insisted on a partnership arrangement before the agency would provide samples or support for their antivenom project, the New Generation Muthea Antivenom. Following their refusal, the researchers say funding proposals for their innovation were rejected without due reason.

They further accused public officials of misusing office to block their progress and obstruct their patent rights. A mediation attempt by the Commission on Administrative Justice (CAJ) also failed after what they described as a misdirected referral by the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC).

While tabling the petition in the Senate, Busia Senator Okiya Omtatah said the matter raises broader questions about how Kenya treats local innovators. “The petition seeks to ensure the innovators’ rights are protected, investigate misconduct by public officials, suspend any officials found to be obstructing justice and establish national protections and policy for indigenous innovation,” Omtatah told fellow lawmakers.

According to the petitioners, the hostility from government institutions goes beyond funding rejection. They allege that they have faced threats, coercion to surrender their formula and patents, legal intimidation, and calculated efforts to damage their reputation. Senator Omtatah claimed that red tape has been weaponized against them, with public officials delaying necessary approvals and support, despite the innovation reportedly saving lives in communities like Wamunyu in Machakos and Kinango in Kwale County.

The researchers said their anti-venom has been safely used for over a century in these regions, reportedly with zero death outcomes for all snakebite victims treated using the Muthea formula. Yet, they say they have been blocked from scaling the treatment due to a lack of institutional backing and interference from powerful interests.

They also raised concerns about alleged unfair collaboration between KEMRI and an inexperienced individual described as a farmer, after the researchers’ own formulation details were disclosed. The petition further states that clinical trial information involving KEMRI and the Institute of Primate Research (IPR) has been kept secret, raising transparency concerns.

They also claim that the Director General for Health and other key government offices denied them due process in reviewing their application, while instead giving support to a rival antivenom product that they say is cheaper but problematic.

“This isn’t just about one product. It’s about how we treat innovation in Kenya. Kenya must be a country where bold ideas are nurtured; not stifled. Where innovators are empowered; not extorted,” Omtatah said.

Snakebites remain a serious public health issue in Kenya. According to the Institute of Primate Research, approximately 20,000 people are bitten by snakes each year. Of those, around 4,000 die, and another 7,000 suffer long-term health effects, including paralysis.

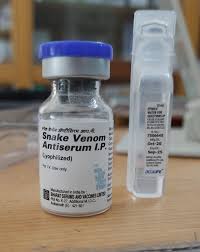

Most of the antivenoms currently used in Kenya are imported from countries like Mexico and India. However, health officials admit that nearly half of these imported treatments are ineffective because they are not suited to Kenya’s unique snake species. Experts say snakebite treatments must be formulated using venom from local snakes to work properly.

In response to the crisis, Kenya is set to open a KSh 1.8 billion anti-venom manufacturing plant. The facility will be operated by the Kenya Snakebite Research and Intervention Centre in partnership with Costa Rican experts. The plant, located in Naivasha, will focus on producing region-specific and affordable antivenom using modern research techniques.

While the move is expected to improve access to quality snakebite treatment, the Machakos researchers argue that it should not come at the cost of sidelining or suppressing traditional, locally developed therapies that have already shown success.

They are now urging the Senate and the broader Parliament to not only protect their rights but also establish clear policies and support systems for Kenyan-led innovations, especially those rooted in indigenous knowledge and experience.